14/7/07

8/11/06

23/10/06

19/10/06

17/10/06

8/10/06

Rugged Pathways to a Simpler Time

Sometime in the last year or so someone put up a sign. Between it and what remains of a rough-hewn wooden milking shed, forsaken now for mobile machines, the path plunges between two rows of hydrangeas with bright blue flowers as plump as muskmelons, and the inevitable deposit that marks it as a regularly traveled cow path.

The Azores — and Sγo Jorge particularly — are covered with these paths. They are called canadas or caminhos and they crisscross the rugged Azorean landscape, bisecting pastures and linking towns and villages. On Sγo Jorge, they provide the only access — except by sea — to some of the island’s fajγs, seaside villages built on the flatlands created from the subsidence of the volcanic peaks.

In recent years, the authorities in the Azores, a semiautonomous region of Portugal in the Atlantic, have begun marking these paths, hoping to attract tourists willing to hike up and down the very edge of Europe. I have been coming to Sγo Jorge since 1991, the year I married an ιmigrι born on the island, and back then I would hear of some of these paths, like lore, from my wife’s relatives. Others we encountered simply by starting down a village road, which would ultimately devolve into a foot-trail and then descend into the verdant ravines that cleave the island.

One of the first I trekked began in the village of Santo Antγo, where my father-in-law, Josι Xavier, grew up, and ended in Cruzal, the village of Teresa Luis, my mother-in-law. The walk is only two miles or so, but steep in places, and retracing his footsteps I came to appreciate the effort he made to court this woman some 50 years ago.

The paths are not exactly a step back in time, but at least a long walk into a simpler place of natural beauty, unspoiled but for the necessity of earning a living. On Sγo Jorge this means milking cows and making a pungent cheese named for the island.

The longest trail winds for several miles along the island’s uppermost ridge, passing the highest peak, Pico da Esperanηa, nearly 3,400 feet above sea level, at the top of which you will find a small lake nestled in a meadow of mountain grass and flowers. From here, on a clear day, you can see the four other islands of the Azores’ central group.

Another begins at Fajγ dos Vimes, a village on the southern coast. Hugging the coast, the path leads to Fajγ dos Bodes, but a couple of years ago a rockslide severed the path, which has yet to be restored I picked up the path farther on, past a riotously pink church.

Starkly visible across the strait is the island of Pico, named after its dominant geographical feature, a perfectly conical volcano that is the highest point in all of Portugal at 7,713 feet. (In 2004, I climbed Pico with a guide and ate lunch on the summit, sitting above the clouds, warmed by volcanic vapors emanating from a vent.)

The trail jackknifes back and forth, up and down before ending three miles later — and more than 1,800 feet below — in the Fajγ de Sγo Joγo, an assemblage of whitewashed, red-tile-roofed houses. The village has a chapel with 19th-century cast-iron bells and a forlorn but friendly cafe that serves ice cream and ice-cold beer.

Each fajγ has its own semitropical microclimate, and the Azoreans long ago carved terraces into the hillside where they still grow potatoes, bananas, figs, taro and coffee, as well as grapes for wine made in ancient stone presses. Once I met a man on the road who insisted I try his homemade white, a sturdy, earthy vintage that by the third glass left me woozy. (There’s a road down to Sγo Joγo, and in such circumstances it is best to call a taxi.)

The best of the three marked paths — there are four now — is the one that begins at the old milkshed and rows of hydrangeas and leads from the island’s ridge to the Fajγ da Caldeira de Santo Cristo, famous for its lagoon and the cockles in it (the only place in the Azores where they live). Because of the cockles’ scarcity, the locals are allowed to harvest them only from Aug. 15 to May 15. Five swinging gates punctuate the trek. They are fashioned from local wood in warbled designs that recall Gaudν and are perfectly balanced to swing shut, though you are asked to make sure they close so that cows do not escape from field to field.

The hills are covered in dense forests of heather and cedar, interspersed with steep pastures. On some trips I have met herders or other tourists, but last year we descended in solitude. The clouds above us did not obstruct the view of two other islands, Terceira to the right and Graciosa to the left.

The first stone house on the path appears more than an hour later. It is abandoned, probably after the earthquake on New Year’s Day 1980, which devastated much of the island and hastened emigration. Just past it, however, is another house, newly painted, a sign that life here perseveres.

The path crosses a stone bridge, and another trail, barely discernible, leads off to the right, dropping into a grove of dragon trees. It twists around two boulders and leads to a waterfall feeding a small swimming hole, a perfectly shaded place to rest.

The main path dips, crests and dips again, like a roller coaster. The Fajγ da Caldeira de Santo Cristo appeared. It has only a dozen or so stone houses, nestled at the base of Pico do Brejo, which looms nearly 2,500 feet above. The village’s most visible landmark, aside from the lagoon, is the church, also Santo Cristo, a small stone structure, with a bell tower. It is never locked.

At Caldeira, you have a choice: you can continue walking another three miles to the Fajγ dos Cubres or go back up the way you came. I did that, once. Better to continue past the lagoon, the abandoned cemetery and the mostly abandoned fields of Fajγ dos Tijulos. The path rises and falls again before reaching the Fajγ dos Cubres, which also has a lagoon and a church with an altar made from cork.

A paved road reaches Cubres (though it, too, was swept away a few years ago and was closed for a couple of years), and after a cold drink in the cafe opposite the church, you can ride back to the top of the mountain.

This year, for the first time, the island’s village councils began organizing tours that are led by old-timers. The project is intended to help others learn what I discovered by happenstance: that these old, nearly abandoned paths contain, as a brochure put it, “a memory that is important to preserve.”

VISITOR INFORMATION

WALKING TOURS

Aven Tour (351-295-416-711 or 351-963-219-751; on the Web, only in Portuguese, at www.aventour-net.com) in Calheta, Sγo Jorge’s second town, organizes walking tours on the island.

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

The Hotel Sγo Jorge Garden (351-295-430-100; fax 351-295-412-736; on the Web, only in Portuguese, at www.hotelsjgarden.com) is the biggest and most traditional hotel in Velas, the island’s main town, with double rooms costing 65 euros, (about $85 at $1.30 to the euro) in winter.

The Casa do Antσnio, (351-295-430-330; fax, 351-295-432-008; e-mail antonio@viagensaquarius.com) opened last year in a rambling structure overlooking the harbor in Velas; a statue of a mermaid is perched atop the building. Next summer, prices for a double will be 88 euros and a “quarto da torre” — a room in one of the turretlike towers — will be 100 euros. Doubles in October are 66 euros and only 55 and 65 euros November to March.

Not far away, above the quay, is the Restaurante Marisqueira Clube Naval de Velas (351-295-412-945), which specializes in seafood. Dinner for two costs 30 to 40 euros.

The Quinta do Canαrio (351-295-412-800; fax, 295-412-802; on the Web, only in Portuguese, at www.quintadocanario.com) is a small stone house in Santo Amaro, with a private double with a bathroom for 100 euros and two rooms that share a bathroom at 90 euros each.

(Brexians lair)

by

brexians

στις

23:49

0

of you said:

![]()

4/10/06

3/10/06

30/9/06

The Making of Modern Greece

An international conference at King's College London looks into the Greek experience of nation-building in the 19th century

A visionary, Rigas Ferraios - aka Velestinlis - was behind the 1797 publication in Vienna of a constitution for a future 'Hellenic Republic'. He paid for his ideals with his life shortly afterwards

EVERY Greek and every friend of the country knows the magic date of 1821, when the banner of revolution was raised against the empire of the Ottoman Turks, and the story of 'Modern Greece' is usually said to begin. What is less well known, but almost more important, is that just eleven years later, in 1832, the newly independent state of Hellas was recognised by international treaty, with the full rights of a sovereign nation. Greece was only the second of the new nation-states of modern Europe to be recognised in this way (pipped by just two years by... Belgium).

Historians of Modern Greece have not always paid sufficient attention to this fact, which places the Greek achievement of an independent nation-state, so early in the nineteenth century, in the forefront of the emergence of the modern political and intellectual movement known today as nationalism. Historians of the movement, whose origins are generally supposed to lie in the ferment of ideas that reached its peak before and after the French Revolution of 1789, may learn much from studying the Greek experience during those years. Nationalism is still a very potent force in world politics today - just think of the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, only a few years ago, or the present conflict in the Middle East. Those who try to understand the powerful appeal that the idea of the nation can have over the intellects and emotions of its members ought to interest themselves in charting, much more rigorously than has yet been done, the ferment of ideas that accompanied the birth and early years of the modern Greek state.

The year 1797 saw the publication, in Vienna, of a constitution for a future 'Hellenic Republic' by Rigas of Velestino (sometimes also known as Ferraios). No such state existed at the time, of course, and Rigas paid for his visionary ideals with his life shortly afterwards. But a century later, in 1896, the capital of independent Greece, Athens, was chosen by an international committee as the first venue of the newly revived Olympic Games, an event that established the greatest international sporting fixture of modern times. The achievement of nationhood had not only transformed Greece; it had also very radically changed ways of thinking, both among Greeks themselves and those who interacted with them.

How did this come about? How were the new ideas expressed and disseminated? What were the roles of philhellenes, critics and other observers outside the country? The answers to these and other related questions were sought at an international conference held on September 7-9, at King's College London, under the auspices of the college's Centre for Hellenic Studies, in collaboration with the Institute for Neohellenic Research, part of the National Hellenic Research Foundation in Athens.

Print of Rigas' so-called Charta (map)

The theme of the conference was "The Making of Modern Greece: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Uses of the Past (1797-1896)". It attracted over 30 speakers, from institutions in Austria, France, Italy, and Russia, as well as from Greece, the UK and the US. The focus throughout was not so much on the well-known milestones on the way to the creation of the Greek nation-state, but rather on the thought-processes that underpinned nationalism and made that achievement possible. Speakers were encouraged whenever possible to bring a comparative dimension to their work so that Greek ideas, attitudes and achievements would be considered not in isolation but in relation to comparable trends elsewhere in Europe and the region.

Under the title "Comparative Nationalism", the concluding panel included Suzanne Marchand (Louisiana State University), a specialist on romanticism and philhellenism in 19th-century Germany, and Samim Akgonul, who researches in social history at the University of Strasbourg in France, and has written on the vexed issue of relations between Greece and his native Turkey during the 20th century. Also speaking in this session was Robert Holland, of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London, who has just published (with Diana Markides) ground-breaking work on successive British 'colonial' confrontations with Hellenism: in the Ionian Islands, in Crete and in Cyprus. Then, from the point of view of a classicist with a strong comparative interest in the way history has been written in modern and ancient times, Henrik Mouritsen, of the Department of Classics at King's, rounded off this session by suggesting that modern Greece has been much more successful than modern Italy in mobilising a vision of the country's classical past so as to capture the imagination and the loyalty of its citizens.

Other panels tackled such subjects as 'Religion and Nationalism', the juxtaposition of western European perspectives on emerging Greece with emergent Greek perspectives on their neighbours in the Balkans and Europe, and the nature and wider impact of the perennially controversial 'Language Question' in Greece. Archaeology, and attitudes to the progressive uncovering of a sometimes unfamiliar past, formed the backbone of two sessions. In others, speakers addressed questions of political and social developments (with particular reference to the Ionian Islands under British rule from 1815 to 1864), the role of literature in shaping the national imagination, and parallel developments in the daily press, in opera and music, in visual arts and in public architecture.

The first of two 'keynote' speeches was given by Paschalis Kitromilides, director of the Institute for Neohellenic Research and professor of Political Science at the University of Athens, who called for the study of Greek intellectual history to be 'canonised', through wider recognition by scholars in other countries dealing with comparative and theoretical issues. The second, by Anthony D Smith, applied the insights of the one of the most influential and original political scientists of the day to the specific case of Greece. A notable aspect of the conference was the interaction between distinguished experts in their respective fields (including, among others, Mark Mazower, Charles Stewart, Michael Llewellyn Smith, who was recently British ambassador to Greece, Peter Mackridge, Alexis Politis and Dimitris Tziovas) and younger scholars, now completing their doctorates or in junior academic positions, who will take the subject forward into the next generation.

So, what does the Greek experience of nation-building in the 19th century have to teach academics and policymakers in the globalised world of the 21st century? I cannot claim that our discussions in London produced any short, sharp, 'sound-bite' answers to the questions raised by the conference. But I do believe that, thanks to the many scholars who took part and to an excellent organising team on the ground, something worthwhile was achieved in defining the questions that future research will have to answer. In these fields of enquiry, just as in the 'hard' sciences, working out how to formulate your question properly can already take you a long way towards finding the answer.

* The writer is Koraes Professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King's College London. He contributed this review to the Athens News

ATHENS NEWS , 22/09/2006, page: A40 Article code: C13201A401

(Brexians lair)

by

brexians

στις

16:09

0

of you said:

![]()

26/9/06

A Touch of Greece, and a Spatter of Grease

ΤΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟ ΔΑΙΜΟΝΙΟ ΣΤΗΝ ΑΜΕΡΙΚΑΝΙΚΗ ΠΡΩΤΕΥΟΥΣΑ

When Homer Bacas moved his family to the Virginia suburbs in 1960, he bought a brick rambler on an acre in Fairfax County. It was on a dirt road with a hand-lettered sign that read "Atheans Road."

He promptly went to the courthouse and got county officials to agree to give his street the name "Athens Road." The faulty spelling of an early land surveyor was corrected, but it was also Bacas's sly way of putting his Greek heritage on the county map.

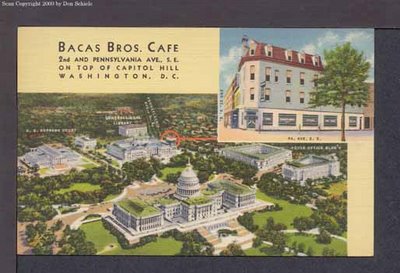

His father, Angelos Bacas (pronounced BACK-us), came to Washington as a young man and eventually brought three brothers with him. They ran a series of restaurants across the city, including the Bacas Bros. Cafe on Capitol Hill.

In 1919, Angelos Bacas opened the evocatively named P.O. Visible Lunch on North Capitol Street. The "P.O." came from its location near the main post office and the Government Printing Office; "Visible Lunch" referred to the glass-front cases that allowed customers to watch food being prepared in one of the city's first cafeterias.

It was part of a quainter, more relaxed Washington that was never forgotten by Homer Angelos Bacas, who died Sept. 9 of a stroke at 82.

An affable man with a ready quip and an inability to sit still -- "Do something, even if it's wrong," he liked to say -- Bacas recalled a city of long-vanished Jewish, Irish, Italian and Greek enclaves. He rode streetcars all over town for a nickel, and the public school system was one of the best in the country.

The first home he could remember was at Eighth and M streets SE in Washington, and one of his earliest memories was of aviator Charles Lindbergh as he emerged from the gates of the Washington Navy Yard across the street. For a year or two, Bacas's parents ran a hotel in Cumberland, Md., until a fire burned the mountaintop inn to the ground. The family then moved back to Washington.

As a young man, Bacas and his boyhood friend Bowie Kuhn, who later became the commissioner of Major League Baseball, helped operate the scoreboard during Washington Senators games at the old Griffith Stadium.

When Bacas graduated from Roosevelt High School, the principal summoned him and his father to a meeting, concerned that the teenager was getting in with the wrong crowd. The principal and Bacas's father decided to send him to Virginia Tech, far from the temptations of the city.

Father and son rode the train to Blacksburg, and once they got there, Bacas began to panic.

"What am I going to do for money?" he asked.

"Get a job," his father said, boarding the train back to Washington.

After two years of waiting tables and studying engineering at "VPI" -- Bacas insisted on using the old name of Virginia Polytechnic Institute -- he enlisted in the Navy during World War II. After the war, he returned to a bustling Washington and worked in the family's restaurants, becoming a skilled short-order cook. He would make breakfast for his family throughout his life.

In 1949, he married Estelle "Chickie" Mandris and began to look for a way to make his own way in the world. He began an extermination business, working primarily in restaurants, then in 1960 opened the Bacas Co. Real Estate, a Fairfax County brokerage firm that he ran until he retired four years ago. He focused on commercial properties and helped develop the Jermantown Square shopping center in Fairfax City.

As he and his wife raised their four daughters, they watched their community change from its early rural character -- his first neighbors raised horses and goats -- to a dense suburb.

The Bacases brought a touch of Greece to Athens Road every spring with a Greek Easter celebration for the extended family, complete with roasted lamb, eggs and all the traditional trimmings.

In 1972, Bacas and 22 of his relatives made a pilgrimage to Greece. They visited three of the four villages that his grandparents had come from, but as they approached the fourth -- his mother's home town -- she stopped and refused to go on. She preferred to remember the village she knew as a child, before time had wrought its inevitable change.

Six years ago, Bacas suffered a stroke that affected his speech, and his wife died in 2004. But until the end, he never lost his storytelling gift or his sunny view of life.

"My dad truly believed that everything he had was the best," said his eldest daughter, Diane Hoffman. "He was never jealous and never pined for what other people had."

For the past two years, he had a kitchen in his apartment at a retirement home. Each morning, he got up to make eggs for breakfast, just the way he had learned at the P.O. Visible Lunch so long ago.

(Brexians lair)

17/9/06

A WORLD OF COFFEE..

The Americas

Coffees in this region commonly have winey acidity, rustic flavors and intense aromas.

Ethiopia

Situated on the eastern coast of Africa south of Ethiopia, Kenya lies with a leg on each side of the equator. The soil of the land is rich with volcanic minerals and home to some of the finest coffee trees in the world. Kenyan farmers are meticulous in the care of their crops. Specialty coffee is harvested in nurseries where it can be carefully nurtured. It is only after the coffee tree is 18 months old that it is transferred to cultivated ground and planted. There it continues to be tended for 3 more years. During the harvest the red berries are picked selectively by hand as soon as they are ripe, to ensure the highest quality.

Yemen is situated at the southwestern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. The coffee growing highlands of Yemen are not desert, on the contrary they are rugged mountains, intensely terraced and cultivated, with austere stone villages rising from hilltops like dreamlike extensions of the rock. Found along the Red Sea, Yemen was home to some of the world's earliest cultures. Using traditional methods created over 400 years ago, Yemeni people still cultivate much of their coffees without the use of pesticides, herbicides or chemical fertilizers. Yemeni farmers and small traders know their coffees with the deep cultural intimacy that develops when coffee is a way of life rather than a mere crop.

The Pacific

Papua New Guinea

(Brexians lair)