A Touch of Greece, and a Spatter of Grease

ΤΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟ ΔΑΙΜΟΝΙΟ ΣΤΗΝ ΑΜΕΡΙΚΑΝΙΚΗ ΠΡΩΤΕΥΟΥΣΑ

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, September 24, 2006

When Homer Bacas moved his family to the Virginia suburbs in 1960, he bought a brick rambler on an acre in Fairfax County. It was on a dirt road with a hand-lettered sign that read "Atheans Road."

He promptly went to the courthouse and got county officials to agree to give his street the name "Athens Road." The faulty spelling of an early land surveyor was corrected, but it was also Bacas's sly way of putting his Greek heritage on the county map.

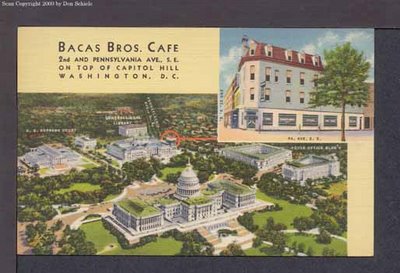

His father, Angelos Bacas (pronounced BACK-us), came to Washington as a young man and eventually brought three brothers with him. They ran a series of restaurants across the city, including the Bacas Bros. Cafe on Capitol Hill.

In 1919, Angelos Bacas opened the evocatively named P.O. Visible Lunch on North Capitol Street. The "P.O." came from its location near the main post office and the Government Printing Office; "Visible Lunch" referred to the glass-front cases that allowed customers to watch food being prepared in one of the city's first cafeterias.

It was part of a quainter, more relaxed Washington that was never forgotten by Homer Angelos Bacas, who died Sept. 9 of a stroke at 82.

An affable man with a ready quip and an inability to sit still -- "Do something, even if it's wrong," he liked to say -- Bacas recalled a city of long-vanished Jewish, Irish, Italian and Greek enclaves. He rode streetcars all over town for a nickel, and the public school system was one of the best in the country.

The first home he could remember was at Eighth and M streets SE in Washington, and one of his earliest memories was of aviator Charles Lindbergh as he emerged from the gates of the Washington Navy Yard across the street. For a year or two, Bacas's parents ran a hotel in Cumberland, Md., until a fire burned the mountaintop inn to the ground. The family then moved back to Washington.

As a young man, Bacas and his boyhood friend Bowie Kuhn, who later became the commissioner of Major League Baseball, helped operate the scoreboard during Washington Senators games at the old Griffith Stadium.

When Bacas graduated from Roosevelt High School, the principal summoned him and his father to a meeting, concerned that the teenager was getting in with the wrong crowd. The principal and Bacas's father decided to send him to Virginia Tech, far from the temptations of the city.

Father and son rode the train to Blacksburg, and once they got there, Bacas began to panic.

"What am I going to do for money?" he asked.

"Get a job," his father said, boarding the train back to Washington.

After two years of waiting tables and studying engineering at "VPI" -- Bacas insisted on using the old name of Virginia Polytechnic Institute -- he enlisted in the Navy during World War II. After the war, he returned to a bustling Washington and worked in the family's restaurants, becoming a skilled short-order cook. He would make breakfast for his family throughout his life.

In 1949, he married Estelle "Chickie" Mandris and began to look for a way to make his own way in the world. He began an extermination business, working primarily in restaurants, then in 1960 opened the Bacas Co. Real Estate, a Fairfax County brokerage firm that he ran until he retired four years ago. He focused on commercial properties and helped develop the Jermantown Square shopping center in Fairfax City.

As he and his wife raised their four daughters, they watched their community change from its early rural character -- his first neighbors raised horses and goats -- to a dense suburb.

The Bacases brought a touch of Greece to Athens Road every spring with a Greek Easter celebration for the extended family, complete with roasted lamb, eggs and all the traditional trimmings.

In 1972, Bacas and 22 of his relatives made a pilgrimage to Greece. They visited three of the four villages that his grandparents had come from, but as they approached the fourth -- his mother's home town -- she stopped and refused to go on. She preferred to remember the village she knew as a child, before time had wrought its inevitable change.

Six years ago, Bacas suffered a stroke that affected his speech, and his wife died in 2004. But until the end, he never lost his storytelling gift or his sunny view of life.

"My dad truly believed that everything he had was the best," said his eldest daughter, Diane Hoffman. "He was never jealous and never pined for what other people had."

For the past two years, he had a kitchen in his apartment at a retirement home. Each morning, he got up to make eggs for breakfast, just the way he had learned at the P.O. Visible Lunch so long ago.

(Brexians lair)

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου